Faculty Tips and Insights

Building Trust

Contribution from Dana Sumpter, OTM

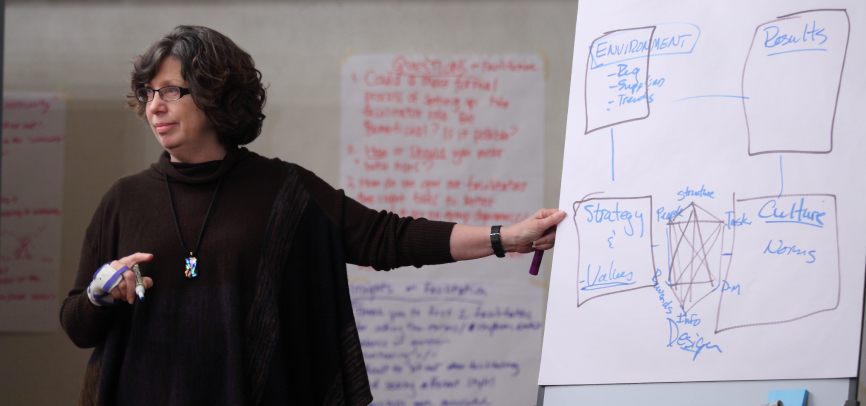

I view building trust with students as a crucial way to effect the learning process. This is particularly important given the nature of the topics that I teach, including cross-cultural management and leading teams – the dicey, complicated people stuff. To start our course, I share information about myself, and similarly ask for information about each student. We do so live during the first class session, so that the “get to know you” time is embedded at the very beginning before we get to work. I post a slide with symbols of my past universities, cities, and hobbies; summarize some of my international experiences and travels; describe my professional experience; and share a picture of my kids. I describe my career path and why I do what I do, why I love teaching and scholarship, and why I am passionate about what I teach and conduct research on. I explain that I have had a varied career path and love talking to students about their careers and future interests, and state that they can feel free to talk with me anytime about their own personal and career ambitions, that I’m happy to be a resource for them, now and in the future.

So, that’s how we start. Then, on an ongoing basis, I conduct “check-ins” at the beginning of each class. I view the start of class as an important opportunity to set the tone for our time of learning together. When on Zoom, I play music before the start of class. It is a different style of music each week; I aim for songs that are positive, uplifting, and/or multicultural. Then as class begins, I welcome them, say “Happy Wednesday, it’s good to see you all!” or something similarly inviting, and then dive into a check-in. This takes different forms. Sometimes I will ask for some participation (“There’s a lot going on lately, let’s all share verbally or post in the chat, what’s one word or phrase that describes how your day was today?”). Sometimes it will be a brief discussion on application of current events (“We are in the midst of an election. Who would like to share an experience they’ve had at work that you would like advice on, or any scenario that we can discuss here related to how this is manifesting in your workplace?”). Moreover, sometimes, it will be more lighthearted, such as sharing a meme or screenshot of different images, and students have to vote for which one represents them or how they are currently feeling. These check-ins can result in laughs, in endearing conversations or consultations, and I hope set the tone for our discussion and activities of the evening to be towards the goal of helping us all to learn more about leadership, management, and people at work. Usually, what is shared easily translates and segues into the course material—although sometimes I have to get a little creative in that transition!

Contribution from Doreen Shanahan, Marketing

- Code word: “Kite”

- 5-minute trust building activity

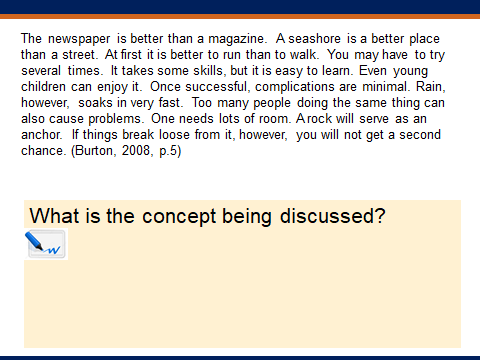

It is important to provide an environment where learners feel it is safe to interact and share, and even take risks because they know they will be supported (Allan & Lewis, 2006). Creating such an environment for adult learners can be particularly challenging, as new learning situations are often met with two conflicting states of mind: “I’m anxious” and “I’m curious” (Taylor & Marienau, 2016). This classroom-tested activity (adapted from Burton, 2008) is both an icebreaker and a way to set up a code word for students to use throughout the term to let the instructor and peers know when they are not able to figure something out and need assistance. The activity can be used in either a face-to-face on online modality. Below is the suggested instructor narrative and slides for the activity for delivery in an online modality.

Begin by asking a student in the class to read paragraph on the slide.

Instructor: What is the concept being discussed? As you listen, write your thoughts using the annotate function in Zoom to the yellow box.

Students are likely to write words down pertaining to course materials they may have been assigned to read in preparation for the class.

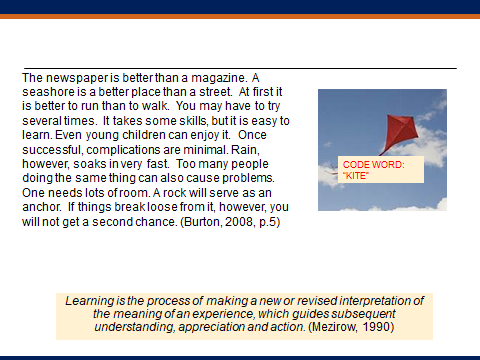

Instructor: Now I want you to think of a kite. [Ask another student to re-read the paragraph.]

Instructor:

Most of you in the room are used to being “in the know” – high achieving professionals, with curious brain’s that drive to figure things out. The feeling of not knowing can cause anxiety, frustration, and even anger. How did the first reading of this passage make you feel? None of the words used in the writing were complex, but as you listened to the words being read, the passage may have seemed nonsensical. Your brains are trying to figure this out, likely with some level of annoyance.

In this course our code word for “I don’t get it” will be kite.

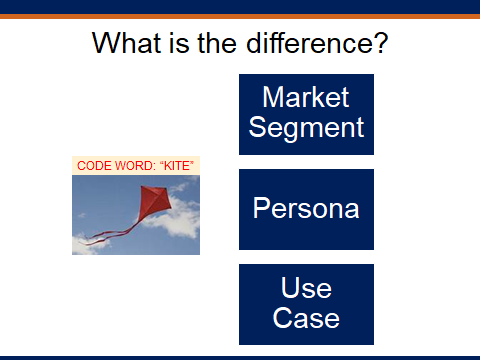

Encouraging Use of the Code Word

As the course progresses, the instructor can encourage use of the code word. Here

are a few examples. Let us say the instructor identifies that a majority of students

demonstrate weak understanding of a concept based on application in a particular assignment;

the instructor might identify this as a “kite” moment. By showing the code word and

symbol on a discussion session slide (see slide below), the instructor creates a safe

environment for revised understanding.

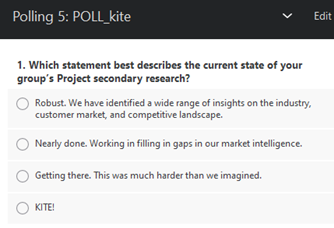

Another way to use the code word is in live session polls. For example, if the instructor

is looking to informally check in on a group project the code word might be used as

one of the answers student can select in the poll, as shown below.

The code word creates a safe environment for students when they need help figuring something out. It is not uncommon to receive several emails (or text) from students each term with the subject line “Kite!” In my experience as an instructor, I have found that when I reinforce use of the code word, students are more inclined to use the term with me and their peers.

References

Allan, B., & Lewis, D. (2006). The impact of membership of a virtual learning community on individual learning careers and professional identity. British Journal of Educational Technology, 37(6), 841–852

Burton, R. A. (2008). On being certain: Believing you are right even when you’re not. New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press

Taylor, K., & Marienau, C. (2016). Facilitating learning with the adult brain in mind: A conceptual and practical guide. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons.

Generating Energy

Contribution from Cole Short, Strategy

Evidence-based Strategy: Teaching Research with Practical Applications

Inspiring students and enriching their learning experience is a core commitment of Graziadio faculty. While faculty expertise varies across practitioner and scholarly lines, our activities reflect our commitment to make a practical impact in the business world. As educators, I think one of the best ways we can make this impact is by inviting our students to engage with the research ideas and real-world problems we regularly tackle. For me personally, my research focus in corporate governance and stakeholder strategy has prompted me to develop a collection of mini-lectures and discussions I refer to as “Evidence-based Strategy.”

The goal of an evidence-based approach is to illuminate how data can inform the effectiveness of business decisions. Each lesson covers a standalone topic that illustrates this link, is relevant, and (ideally) engages students.

For instance, in one module, I walk students through the fundamentals of text analysis to illustrate its business relevance. Using examples from my research and from public companies, I show that the words executives and stakeholders use can have a meaningful impact on business strategy. I then instruct students on how to prepare data for analysis and allow each student to analyze their own selected text in real-time. By succinctly introducing the topic, illustrating its effectiveness, and providing students with an opportunity to assume a hands-on approach, this module enables students to engage with text analysis and see how it informs business.

When evaluating prospective topics, I typically use the following criteria:

- Is it clear? Students should be able to quickly grasp the methodological approach used in the module.

- Is it observable? The topic should be represented with real-world data that can be visualized during class—either in tabular or graphical form.

- Is it useful? The topic discussed should have a direct or indirect impact on organizational outcomes that students can identify.

- Is it engaging? The topic should be relevant to the class session and contemporary business issues, and students should feel comfortable and eager to engage with it.

Using this framework, additional topics I have incorporated include selecting crisis management strategies using regression, evaluating CEO quality using variance partitioning, and informing strategic decision-making with machine learning algorithms.

As faculty, we can use data from ongoing research projects, professional connections, and other researchers to illustrate important concepts. The goal of this pedagogical tool is to play to our strengths in order to inspire and enrich student learning, and as such, opportunities abound.

Contribution from Mark Allen, OTM

My challenge was that I had two 2-unit BSM courses this fall and each was scheduled to meet from 8 am to 5 pm on three Saturdays. It is hard enough to keep students engaged for 8 hours on a Saturday when we’re all in the same room, so I knew that 8 hours on Zoom would violate the constitutional ban on cruel and unusual punishment. Out of a desire to be creative and avoid 8 hour sessions (for both the students and me), I decided to try a couple of new ideas.

First, I pre-recorded three videos. The first was a course overview in which I told the students what the course was about and what to expect. Then I recorded a video describing the course schedule in detail. In this video I told the students the topics we would cover and the expectations for each of our sessions. The final video was about the course assignments. I gave detailed instructions about each of the assignments.

These three videos accomplished a number of things. First, they told the students everything they needed to know about the course. By the end of the third video, I had gone through everything that is in the syllabus. These videos took the place of the first 60-90 minutes of each course. By doing this on video, I was able to shorten our synchronous class times. As an added bonus, two of the three videos were recorded in such a way that I could use the same videos for both sections of my course (the video about the class schedule had to be customized for each section). These videos were all posted about 3 weeks prior to the course start date (along with the syllabus) to give the students a chance to familiarize themselves with the course.

I also put out a call for other professors to pre-record guest speaker sessions for my class. I was extremely gratified at the response to this request. Kevin Groves recorded a session on leadership. David Crowley sent a video on culture. Tom McCluskey provided a recording on strengths-based management. In addition, Steve Gibson did a video about corporate social responsibility. (And a friend of mine who teaches at Whittier College did a piece on decision-making). These videos were typically posted about two weeks before they were due to be discussed in class.

These videos were a terrific addition to the course. Instead of just hearing from me, the students were able to benefit from the expertise of five other outstanding professors. While we have all complained about the constraints of having to teach 100% online, having five guest speakers in a 2-unit class is something that would not have been possible in a 100% face-to-face class, so the students actually received a benefit from having to do this course online.

Additionally, these videos enabled me to transfer some of the contact hours from synchronous to asynchronous. Rather than having to do 8-hour Saturdays from 8 am to 5 pm, I reduced the synchronous times to a more manageable pair of 3-hour sessions each Saturday (9-noon and 1-4). Moreover, as an added bonus, the videos are “evergreen” and I can (and will) use them in future offerings of the course, whether online, on-ground, or hybrid.

In this case, the necessity of having to move my classes on line was the mother of a couple of very useful inventions.

Facilitating the Learning Cycle

Contribution from Jillian Alderman, Accounting

A key learning objective in accounting courses is for students to develop a firm grasp of the “language of business”. This requires a strong foundation of knowledge in the terminology, definitions, and concepts at the core of this language. Meeting this particular learning objective can be somewhat tedious for students, who are eager to explore direct applications and practical experiences. However, skipping this foundational step of obtaining declarative knowledge can limit their applied learning experiences in the course.

Gamification is one useful strategy that I have adopted to motivate students and facilitate the acquisition of declarative knowledge. One excellent example of this is the “Kahoot!” app, which I utilize during class to quiz students on concepts. This acts as an attention check and a fun opportunity for the students to interact and compete against each other to “win” the game. The software also records the students’ scores, which can be downloaded by the instructor in Excel to provide a measure of participation and knowledge acquisition. Regardless of their academic discipline faculty can use the app to take advantage of the benefits associated with gamification.

Before class, I create the quiz on the Kahoot website, using my own multiple choice and true/false questions inspired by course material. When I’m ready to start the quiz, I share my screen and open the quiz to begin (Helpful tip: Be sure to share your sound so students can hear the music). Students then login to the quiz using the free Kahoot app on their mobile devices. As each question comes up on my shared computer screen, students earn points in the game by selecting the correct answer option on their mobile device. They also earn more points for answering the questions quickly. After each question, the correct answer shows on my shared screen, along with a count of how many students answered each option. This provides a moment for me to review the answer and reinforce the concept.

One fun aspect of this game is the leaderboard, which displays the “Top 5” scores after each question. Students love the competitive aspect of this app, as they can observe how the leaderboard changes during the game. At the end, the software plays celebratory music and displays the top three student names on a podium.

You can explore the “Kahoot!” software at kahoot.com by creating a free account. The website contains a series of helpful videos that demonstrate how to utilize the software in the classroom. The downloadable app for Apple and Android devices is required for students to participate.