Organization Development Specialization Consequences

A Cold, Hard Look in the Mirror

Written by Dr. Christopher G. Worley, Dr. Kent Rhodes, Jill Shaver, and Dr. Ann Feyerherm

As Organization Development practitioners, we all want very badly to be a part of the solution, not part of the problem. And as authors, we believe strongly that OD is the solution to many of the diverse challenges facing our world. But we also worry that OD is not nearly close enough to delivering on its promise. We believe that OD is a system-wide application and transfer of behavioral science knowledge to the planned development, improvement, and reinforcement of the strategies, structures, and processes that lead to organization effectiveness. In short, OD was (and is) an integrated process intended to build an organization’s capacity to change and adapt under humanistic values of learning, participation, and democracy.

As we’ve participated in and watched the field grow, we believe that this integrated and holistic experience has been fragmented by the same dynamics that upset the retail industry. Big box retailers like Costco, Walmart, and Target – innovations themselves –started out as integrated experiences. You could purchase almost anything you needed in one place. But that experience was disrupted by the “category killers.” In caricature, category killers were specialists. They took a row from a Costco warehouse (a category) and specialized in it. The office supply row became Staples or Office Depot; the tools row became Home Depot; the liquor and beverage row became BevMo. It was a compelling innovation because the category killer offered a broader selection of products than Costco for roughly the same price. The differentiated approach worked. Many of the category killers were very successful – some still are – but seriously challenged the one-stop shopping experience.

Importantly, in breaking up the integrated experience, a number of secondary and unintended

consequences emerged. To get everything we wanted, we endured increased traffic congestion,

stress, and pollution, higher transportation costs, less time with the family, and

the collapse of malls and the mall experience (if you liked that sort of thing).

…like the category killers, these OD concentrations have grown exponentially, gobbled up by busy executives and managers looking for nifty solutions to pressing issues.

We believe an analogous process is happening in OD. The end-to-end experience of entry/contracting,

diagnosis, intervention, implementation, and evaluation – collectively known as OD

– is being sliced and diced into discrete, specialized offerings. Today, the fully

integrated, system-wide, and capability building version of OD is rarely taking place.

Instead, the entry/contracting process became Block’s Flawless Consulting product,

and more importantly, the change management process became heavily routinized. Today’s

market is flooded with change management tools, frameworks, approaches, and methods

“to make change easy.” At the same time, internal and external OD practitioners now

specialize in coaching, employee engagement, agile teaming, lean/six sigma, team effectiveness

(what ever happened to team building?), and diversity/equity/inclusion.

So while change management and coaching are part of OD, they are not entirely OD because they don’t embrace the integrated process. Coaching is not system-wide; it focuses on certain individuals. Change management doesn’t transfer knowledge and skills, and it’s not about development. OD was never intended to be a set of discrete, independent specialties.

But like the category killers, these OD concentrations have grown exponentially, gobbled up by busy executives and managers looking for nifty solutions to pressing issues. Reflecting core OD strengths like personal growth, coaching has exploded with schools, professional associations, and certification processes. Focusing on the organization’s desire to “get stuff done,” change management consulting firms and internal centers of excellence are common. Tools and processes, certifications, conferences, and LinkedIn and Facebook groups have proliferated. Both coaching and change management have developed competency models so that others can join in. Because of concentration, organizations now have a much broader selection of organization change solutions from which they can choose. What could be wrong with that?

Well, a cold, hard look in the mirror suggests that concentration has produced important, unwanted, and unintended consequences.

Transform Your Career Globally: Apply Now to the Leading Hybrid MSOD

Pepperdine's top-ranked MSOD program blends academic excellence with real-world application.The future of leadership is rooted in human connection and organizational agility. Join a global network of professionals and gain hands-on, experience-driven education with one of the most respected programs in the field.

Get in Touch

Fill out the Request Information form to learn about the opportunities that await you as a student at Pepperdine Graziadio.

Start Your Application

Ready to start your journey to Pepperdine Graziadio? Begin your application today to take the next step towards your future.

A Real or Spurious Relationship?

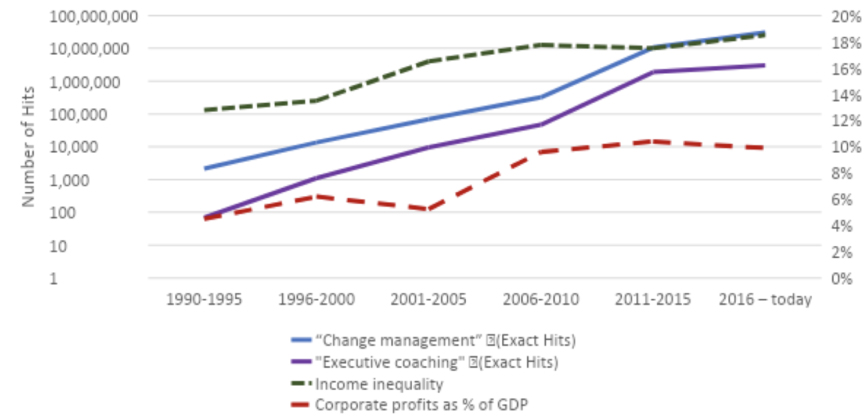

The chart (below) graphs the rise of coaching and change management in terms of google hits as well as the rise in income inequality and corporate profit concentration. On the left axis are the “number of hits” (log scale) over specific five-year periods (for example, Jan 1, 1990, to Dec 31, 1995). We used “exact” terms to generate the number of hits. It’s a proxy for the level of interest or the amount of attention and resources being invested in a particular topic. On the right axis are percentages for income inequality (percent of income accounted for by the wealthiest 1%) and corporate profits as a percentage of GDP. The data here are by no means perfect, yet we have a sense that they are “good enough” to raise a question about our field.

What's the message? The more we talk about, write about, post, discuss, and perfect specialty change practices, the more unequal and concentrated our society becomes1. As specialist change practices have grown, income inequality and profit concentration – key indicators of social inequality, lack of participation, and decreased democracy – have increased. Although "correlation is not causation," it is worth exploring the association. Could there be a relationship?

In short, concentration fragments the integrity of the integrated learning experience. Interventions became less impactful to the system and enabled alternative motivations and values to control the process. What better way to ensure that diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives lack impact than to create a separate organization that must compete with other change initiatives for leadership attention and resources? In the case of coaching, we know that changing individuals is a weak way to change a system. In fact, we’ve known that since the T-group days. People returning to work after a transformational experience-reported backsliding into old behaviors. Individual change cannot be sustained in a system that does not support the new behaviors, and yet we continue to invest in, tout the importance of, and grow the field of coaching and leadership development. When coaching is evaluated as successful, it is far and away because of self-reports with no measure of system impact. Under such conditions, it is the executive that gets rewarded – increasing the value of the individual – not the overall health of the people in the system. Could coaching be contributing to income inequality?

Who or what benefits from a successful change management process? In the best case,

a change increases meaningful work and performance for all. However, absent a diagnostic

phase – and nearly all change management frameworks lack this quintessential OD step

– any intended change has a good chance of being inappropriate or flat-out wrong.

It could be wrong because the decision-maker doesn’t have the right diagnostic data,

or the change is expected to benefit the decision-maker more than the system. In the

hands of a self-interested power-holder, change management is a convenient, controlling,

check-the-box, ‘I use the latest tool’ process to increase his/her status.

Change management processes figure prominently in the execution of these strategies, and the evidence suggests that decision-makers benefit disproportionately from such events.

That’s obviously pretty harsh stuff. Are our interpretations inaccurate? Are there

alternative explanations? Yes, and they may be equally hard to hear.

It is possible that any apparent relationship is just a chance association, like the positive relationship between full moons and emergency room visits. Coaching and change management do improve managers and organizations, but other forces are driving inequality. You might consider our argument – that successful coaching engagements lead to richer executives, and all that rolls up into an increase in the number of 1%’ers – a bit flimsy. The argument is not so easily shrugged off in the change management case. Managers and executives make consequential decisions, including mergers and acquisitions, digital investments, partnering arrangements, and restructurings. Many of these fail to increase the value of the firm over anything but the short term but line executive pocketbooks with cash. Change management processes figure prominently in the execution of these strategies, and the evidence suggests that decision-makers benefit disproportionately from such events. While the average retention bonus for managers in a merger is between 10-15% of annual salary, typically, 30% of employees are deemed redundant post-merger.

A second possibility suggests that the direction of influence is backwards; it is

the increase in income inequality and profit concentration that is rewarding specialist

change practices. This interpretation might be scarier. As organizations succeed in

gaining power or as the rich get richer, power is preserved through paternalism –

“let me get you a coach” – or by unleashing effective change management processes

on the initiatives that will perpetuate the manager’s (perceived or real) power, prestige,

and pocketbook. And again, OD practitioners are complicit. Rather than engaging in

a diagnostic process that examines the system, we take our daily fee, talk about our

contribution, and neglect to evaluate its impact.

The Rest of the Story

But we didn’t describe this situation to depress you. This is, believe it or not, a hopeful story.

As competition and consumers evolved in the retail industry, category killers began losing their shine. Specialty retailers could only get so good at doing one thing. BevMo can only get so much better in terms of its product mix, service quality, and geographical spread. There’s not a lot of upside potential. More importantly, the big box retailers learned to fight back. Costco enhanced their product selections within a category and got better at curating the few choices it did offer. Consumers learned that the smart retailers stocked products with good price/value ratios. In the end, many category killers couldn’t compete, and people just got tired of driving and sitting in traffic. It’s not good for the environment, and it’s a waste of time.

As a field and as MSOD practitioners, we can get ahead of this curve. Specialists can realize that there’s not a lot of upside potential in being a one-trick pony and begin offering a fuller range of value-added services. How much better can coaching get, especially if you want to do work with impact? How much better can our processes of cajoling people into going along with a change they had no choice in making, doesn’t improve the capacity of the organization or its members, and doesn’t improve the effectiveness of the system get? Most coaching and change management professionals are scrambling for ways to differentiate themselves through certification – and the only winners in that game are the professional associations.

Nor do we have to wait for executives to realize they are paying too much for so many

experts (although it appears that it takes them a long time to realize this given

the price tags charged by big consulting firms, and we suspect a darker psychological

enablement and political process is at play). We can begin to act in service of our

values, the field, the organization, and its stakeholders, and not in service of the

powerful elites.

OD was meant to be an integrated, end-to-end, development experience leading to learning, improved capacity for change, and increased effectiveness.

We can – quite simply and as change experts - insist on diagnosis before intervention.

“I’d love to provide you with outstanding coaching services – but what data is leading

you to the conclusion that coaching will help?” “That sounds like a great change;

let’s look at how it aligns with the strategy and works with other changes to support

the whole system.” These are tough stances to take when money is on the table, but

they are ethical ones.

Moreover, broadening our services to resemble the original and integrated development orientation of OD is not hard. Concentration fragments OD’s impact when it’s practiced independently of the other concentrations. If you are an internal practitioner, executive coach, or change management specialist, form a team. Gather specialists in strategy, facilitation, coaching, and interventions, and figure out (diagnose) where the organization needs development and capability building the most. Then, in concert with leadership, integrate your concentrations in service of people, communities, and the organization.

OD was meant to be an integrated, end-to-end development experience leading to learning, improved capacity for change, and increased effectiveness. Isn’t that what’s needed now? In a world being disconnected by a pandemic, warming itself into another global crisis, and being jolted into awareness of racism, specialized change practices are not going to solve the problem. What’s needed is a process of change that builds capacity by embracing diversity and focuses on the health of whole organizations and the communities they serve.

1We also ran the same analysis using the term “OD” as a search topic. Like change management and coaching, there is a positive – but not significant – relationship with income inequality/corporate profits.

Pepperdine's top-ranked MSOD program blends academic excellence with real-world application.The

future of leadership is rooted in human connection and organizational agility. Join

a global network of professionals and gain hands-on, experience-driven education with

one of the most respected programs in the field. Fill out the Request Information form to learn about the opportunities that await

you as a student at Pepperdine Graziadio. Ready to start your journey to Pepperdine Graziadio? Begin your application today

to take the next step towards your future.Transform Your Career Globally: Apply Now to the Leading Hybrid MSOD

Get in Touch

Start Your Application